The “monster” central incisor

Published: September 2012

Bulletin #14 September 2012

The “monster” central incisor

The scene is highly unusual yet typical. Mother has arrived at your office with her 7 year old child and shows you that there is an enormous “monster” tooth just erupted in the upper jaw, at the front of the mouth. It is considerably larger than the normally-erupted, adjacent, contralateral, central incisor and it often has an extra mesial talon cusp which turns at a 60 degree angle towards the palatal or labial and, sometimes, both.

Diagnosis: The first problem is to know what to call it. Several names come to mind. A tooth with a talon cusp is the most likely description, but many would refer to it as a fused central incisor or a geminated central incisor. In the literature, the name dens evaginatus is its official title.

If the adjacent lateral incisor is concurrently missing, then it has been speculated that the central and lateral incisors had fused during their development. Accordingly, a periapical radiograph of the tooth may serve to provide more evidence. If there are two discernible but largely separate roots joined at the cervical area, or if there are two distinct pulp chambers which are partially or completely separate, this would lend support for the diagnosis of fusion. On the other hand, we know that dentitions which exhibit anomaly of tooth shape and size often have missing teeth and a missing lateral incisor is high on the list of likely candidates. But, even if the lateral incisor is present, it is frequently argued that the central incisor is alone in its anomaly and should be referred to as a gemination.

We also know that supernumerary teeth occur most frequently in the anterior midline area of the maxilla and, while these are usually quite separate entities, they may also be fused with the central incisor. So, once again, we have the same range of possible associations for the supernumerary tooth that we have just described regarding the lateral incisor.

The problem: The tooth is far too large and abnormally shaped to include it in the final scheme of the dentition. In general, the tooth is mesiodistally enlarged for most of its length, from the incisal edge through its widest contour and the CEJ and extending a long way down the root. Moreover, the pulp chamber is generally very wide and a pulp cornua may extend into the talon cusp. For all these reasons, interproximal reduction of the tooth cannot be recommended without recognizing that it would cause considerable periodontal damage, well into the subcrestal area of the bone surrounding the root, with the probable need for root canal therapy. Just occasionally, the shape of the tooth may be suitable for it to be disguised as both the central and lateral incisors together, which would require crown recontouring and perhaps a composite addition here or there. In this case, the permanent lateral incisor would then need to be extracted. It becomes clear that, whichever way the conservative approach to its treatment goes, there will be several compromises to make and, in one or more of its aspects, the outcome will be unsatisfactory.

Perhaps the radical approach, i.e. extraction of the monster tooth, will be the answer to eliminating the problem altogether. As always, there is the other side of the coin. If the tooth is extracted, a good provisional replacement will need to be substituted for the medium-to-long-term, until an implant borne restoration may be placed – more than 10 years in the future. Perhaps the possibility of tooth substitution exists, to move the lateral incisor and then the canine across the enormous space left by the extraction. Given the age of the patient, perhaps a 2-phase treatment regimen will be needed or maybe the entire treatment should be left until the patient reaches 12 years of age.

Of course, there are no hard and fast answers to these questions and a plan that suits one case may be entirely irrelevant in another because of the relative weights of the many factors involved. Neither does the literature necessarily help us with disciplined investigations of large samples of these cases, because they are rare and there is no chance of finding enough of them to establish evidence based recommendations. The practitioner must be in a position to make therapeutic decisions on the basis of the findings of his/her clinical and radiographic examination of each individual case, together with ideas culled from published reports of similar cases and the borrowed experience of others.

Case Presentation:

Fig. 1. Clinical intraoral views of the initial malocclusion at age 7.6 years, in August 2007.

An 7.7 year old girl, accompanied by her mother, attended for treatment of a dens evaginatus “monster” central incisor in the right side of the maxilla (Fig. 1). The tooth was very large and almost twice the size of the adjacent tooth in the contralateral central incisor position.

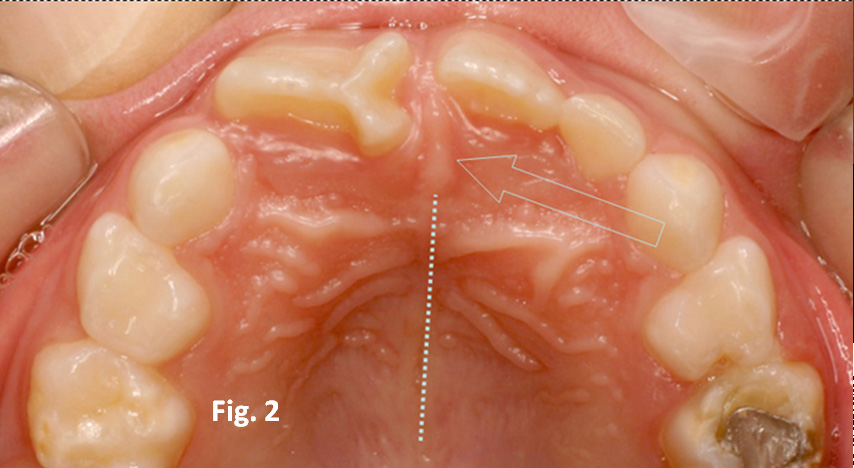

Fig. 2. Occlusal intraoral view of the maxillary dentition and palatal area. The dotted line demarcates the median raphe of the palate and the arrow points to the incisive papilla.

Fig. 3. En face photograph of the patient.

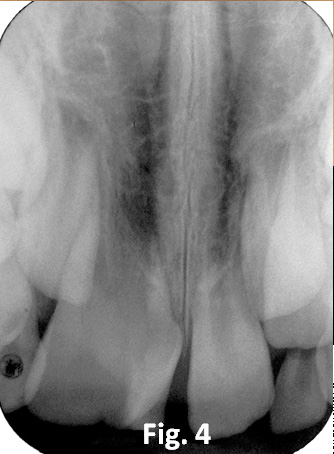

Fig. 4. Periapical view of the dens evaginatus, showing broad crown and root width and large pulp chamber.

The affected tooth exhibited a labial and a palatal mesial talon cusp, each oriented at 120 degrees from the major part of the incisal edge (Fig. 2, 3). The patient was in the early mixed dentition stage, with the deciduous canines and molars in place, together with a single left deciduous maxillary lateral incisor. The four first permanent molars and the mandibular permanent incisors were the only other erupted permanent teeth. The intermaxillary occlusal relations were normal, the incisors edge-to-edge and the mandibular incisors mildly crowded. In the maxilla, there was reduced space for the unerupted lateral incisors, partially because of the size of the abnormal tooth.

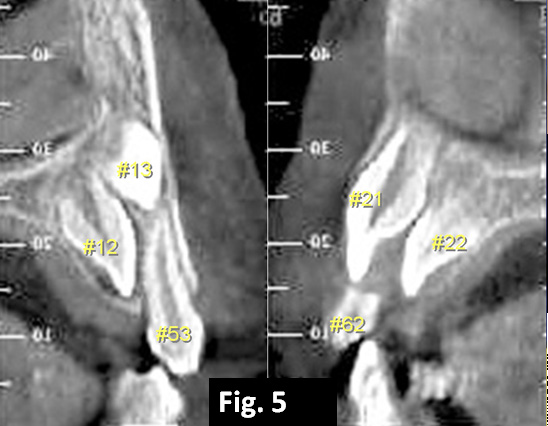

Fig. 5. CBCT transaxial frames on either side of the midline to show the dens evaginatus (#13), the impacted left central incisor (#21), the two permanent lateral incisors (#12 and #22). The right deciduous canine (#53) and left deciduous lateral incisor (#62) can be identified, but the erupted supernumerary tooth is not seen here.

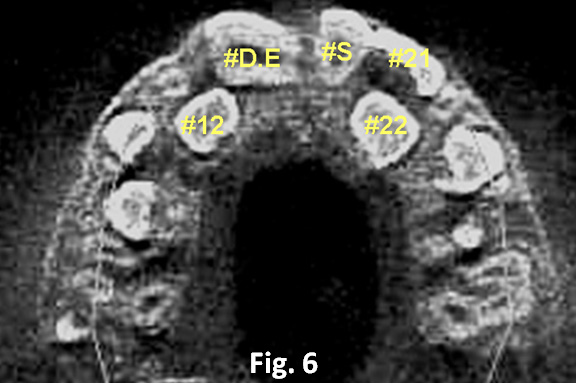

Fig. 6. A CBCT axial frame shows the dens evaginatus (#D.E), the erupted supernumerary tooth (#S), the impacted left central incisor (#21) and both unerupted maxillary lateral incisors (#21 and #22).

The panoramic radiograph showed the presence of all permanent teeth, although additional periapical views of the maxillary anterior area showed superimposition of several unerupted teeth, including a supernumerary tooth. Cone beam computerized tomography (CBCT) was ordered and this produced interesting results (Fig. 4-6). What had been assumed to be an unerupted supernumerary tooth was in fact an impacted left maxillary central incisor of ideal shape and size. Unerupted lateral incisors were identified bilaterally and the tooth that had earlier been considered a small left central incisor adjacent to the dens evaginatus was of poor shape and was clearly an erupted mesiodens, with a smallish and narrow root. On the basis of root development of the permanent teeth, the patient’s dental age was set at 7 years. The dens evaginatus had a wide and enlarged pulp chamber and was extremely broad at its CEJ area, making it impossible to include in the final scheme of the dentition (Fig. 4).

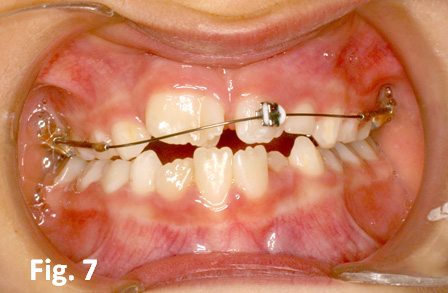

Fig. 7. The initial appliance set-up in September 2007, with a single bracket on the supernumerary tooth. Note the extrusive activation of the anterior portion of the Johnson archwire.

Treatment plan: Because of the inordinate size of the tooth and the edge-to-edge occlusion both mother and child were acutely aware of an ugly appearance and were clearly keen to begin treatment as soon as possible. Furthermore, if the monster tooth were to be extracted, it was felt that this should be done at an age when an edentulous area at the front of the mouth was commonplace and unlikely to cause undue distress to the child – after all, just a few months previously, the deciduous teeth had shed and the space was present before this tooth erupted.

Since the tooth could not be reduced to an acceptable size while maintaining its clinical viability and neither could it be passed off as two teeth, its extraction was prescribed. At the same time, the small and narrow erupted mesiodens which occupied the place of the impacted left central incisor would be moved across the midline to the right side and into the place of the extracted dens evaginatus. This would then create space for the impacted left central incisor and the unerupted left lateral incisor. It was judged that although these two teeth might eventually erupt unaided, the waiting period might be excessively long and a surgical exposure could prove expeditious. The edge-to-edge incisor relation would be treated by proclination of the incisor teeth and a deepening of the overbite. No treatment was planned in phase 1 for the lower jaw. Phase 2 treatment would be initiated following the eruption of the remaining teeth of the permanent dentition.

Fig. 8. Extrusive leveling was achieved 2 months later, in November 2007 and a coil spring was placed between the soldered stop on the left side pieces of the archwire and the distal of the bracket on the supernumerary tooth. At the same visit, the dens evaginatus was extracted.

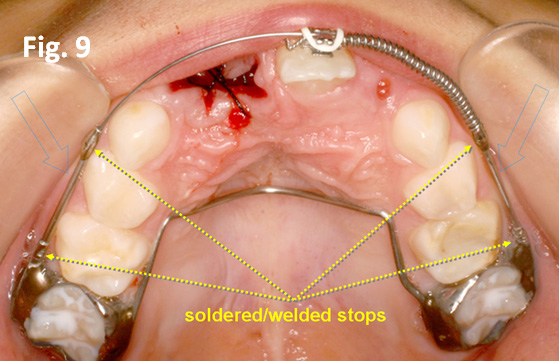

Fig. 9. An occlusal view of the appliance, activated to move the supernumerary tooth to the right, in place. The blue arrows indicate the stainless steel side tubes of 0.020” diameter, which slide fit into the soldered round 0.036” tubes on the molar bands. The welded/soldered stops on the side pieces maintain the existing arch length.

Biomechanics: It was considered important to place the appliance that would move the left-sited and erupted mesiodens to the right side and to reach the point at which mesial force was actually applied, before extraction of the offending tooth. Furthermore, the initial movement of the tooth was deliberately designed to be a tipping movement. The reason for these steps was to achieve as quick a movement as possible and to fill the space of the missing tooth even with a tipped tooth, in order to limit the time that the child would be edentulous.

A rigid palatal arch was soldered to the molar bands and round 0.036” molar tubes were soldered on the buccal side. A single Tip-Edge bracket was bonded to the supernumerary incisor and a modified Johnson twin arch (Fig. 7) was constructed using 0.020” side tubes (with an external diameter of 0.036”) that slotted accurately into the round buccal molar tubes. The anterior portion of the Johnson twin arch carried an 0.020” stainless steel wire, which was ligated into the single anterior bracket. For details of the construction of this appliance, the reader is referred to Bulletin #11, May 2012 on this website. Because of the long span between accurately aligned molar tubes and anterior bracket, together with the oversize slot width, the ligation exerted very little pressure on the anterior tooth. On the second visit, 3 weeks later, the dens evaginatus was extracted and a long expanded coil spring was placed on the archwire, compressed between a soldered stop at the mesial end of the left side tube of the Johnson archwire and the distal of the bracket on the supernumerary tooth (Fig. 8, 9).

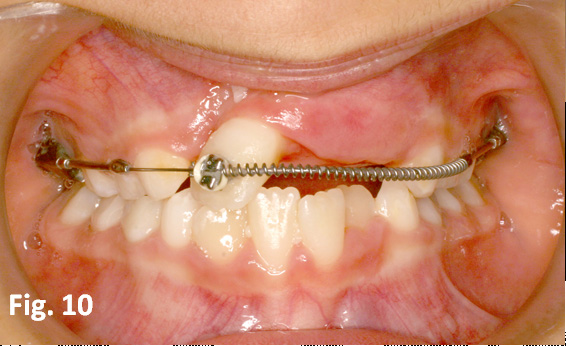

Fig. 10. In January of 2008, the supernumerary tooth had been tipped across the facial midline to a deliberately excessive degree.

Fig. 11. A long curved length of steel tube was substituted for the coil spring to maintain the position of the crown of the supernumerary tooth and an uprighting spring spring placed in the tooth.

Within 3 months and with Tip-Edge brackets, the tooth had moved across the midline area and had been over-tipped into a more distal position than was apparently required (Fig. 10). A long length of curved 0.036” steel tube was substituted for the coil spring, in order to maintain the new position, while a Begg uprighting spring was inserted into the Tip-Edge bracket to move the root of the mesiodens to the right and to upright it more acceptably (Fig. 11).

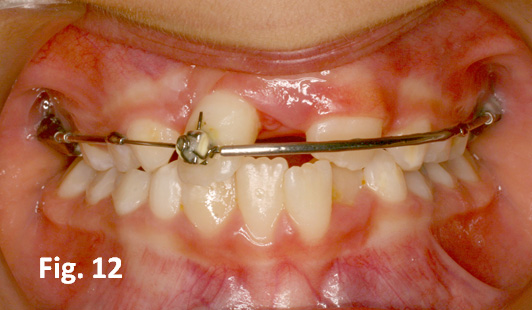

Fig. 12. While uprighting was occurring, the left previously impacted central incisor erupted spontaneously following the provision of space, seen here in April 2008.

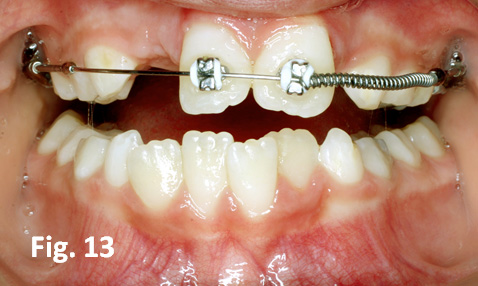

Fig. 13. A bracket was bonded to the newly-erupted tooth and it was pushed mesially into contact with the uprighted supernumerary teeth, seen here in July 2008.

After a further 4 months and given the excessive space that had been created on the left side by this movement, the erstwhile impacted left central incisor began to erupt spontaneously and in timely fashion, to render surgical exposure completely unnecessary (Fig. 12). A bracket was bonded to it and the two front teeth were aligned and uprighted as needed (Fig. 13).

Fig. 14. The lateral incisors erupted spontaneously very slowly over many months. Brackets were placed and the anterior spacing closed, with root uprighting as needed, seen here in August 2009.

Fig. 15. The completion of phase 1 was completed in August 2009 and the appliances were removed to await the eruption of the permanent teeth. Note the poor shape of the supernumerary tooth in its role as the missing right central incisor.

The lateral incisors did not erupt until 7 months later, when they too were bonded, the four incisors aligned and the appliances were removed to be replaced by retainers (Fig.14, 15).

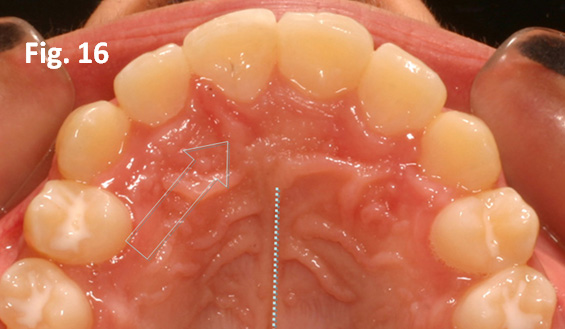

Phase 2 commenced more than a year later, with conventional multibracketed appliances and utilizing the leeway space of the second deciduous molars to align the remaining teeth and correct all other discrepancies, detailing etc. and the appliances removed 16 months later. Removable retainers were placed and the patient was referred to her dentist to improve the shape and size of the mesiodens, to successfully match it to the normal incisor (Fig. 16-18).

Fig. 16. Phase 2 treatment with fully banded appliances began in February 2011 and was completed in June 2012. The dotted line on the occlusal view of the palatal area demarcates the palatal median raphe, while the blue arrow indicates the incisive papilla, which is situated between the supernumerary tooth (formerly on the left side) and the lateral incisor on the right side.

Fig. 17. The anterior dentition is seen here, following minor reshaping and composite addition to the supernumerary tooth to improve its appearance – July 2012.

Fig. 18. The patient in July 2012 at age 12.6 years, following completion of treatment.

It is interesting to note that while the supernumerary tooth had erupted on the left side of the maxillary midline suture and the incisive papilla, moving the tooth several millimeters to the right side had not altered this relation. Instead, the suture and papilla together with the immediately adjacent alveolar bone of the ridge, had themselves deviated to the right side. This may be seen on the post-treatment occlusal view (Fig. 16) which shows the more posterior portion of the midline raphe unaltered, while the papilla has veered sharply to the right. Similarly, in the view from the front (Fig. 17), the apparently swollen and inflamed interdental gingival papilla between the newly simulated central incisor and the right lateral incisor is in fact the previous and now deviated midline labial frenum!

Given well planned and executed tooth movement, together with the finishing touches of a competent restorative dentist, it is most unlikely that even a discerning and perceptive professional will be able to recognize the substitution that has been performed (Fig. 17, 18).

Addendum

Fast-forward to September 2014.

.

.

Fig. 19a-e. The patient has completed prosthodontic restoration of the midline supernumerary tooth which has admirably substituted for the extracted “monster” right central incisor and bonded fixed twistflex retainers have been placed on the lingual side of the anterior segments of both dental arches