The “Classic” Dilacerate Maxillary Incisor

Published: April 2012

Bulletin #10 - April 2012

The “Classic” Dilacerate Maxillary Incisor

In Bulletin #2, published on the website in August 2011 (see Newsletters Archive, on the right side of this page), the extraction of supernumerary teeth that had been the cause of impaction of maxillary incisors was discussed. It was pointed out there that, in the absence of more affirmative action, this procedure alone is unlikely to bring about the spontaneous resolution of the impaction and a normalization of the erupted incisor alignment. Notwithstanding, it is most common for the young patient with an unerupted maxillary incisor to be first referred by the pediatric dentist or GP to the surgeon. Depending upon the Oral and Maxillofacial surgeon concerned, most will accept the patient with the view to removing the supernumerary tooth/odontome and suturing back the flap after completion of the procedure. Extraction of the over-retained deciduous incisors will be unavoidable and the patient will be left with a large edentulous gap at the front of the mouth. Subsequent referral to the orthodontist will usually be made only after many months – sometimes stretching into years – of absence of eruptive progress of the impacted incisor.

Theoretically, leaving the unerupted incisor undisturbed in its intact dental follicle should give the tooth its most favorable environment for it to realize its full alveolar bone resorptive and eruptive potential, but experience recorded in the many published clinical investigations dictates otherwise. Neverthless, some intra-alveolar positional improvement may often occur, as may be seen on follow-up radiographs, which will make the tooth more accessible in a second surgical procedure.

A less common reason for non-eruption of a central incisor and the subject for this month’s bulletin, is the phenomenon known as dilaceration. The historic background to the theories for its occurrence is discussed fully in the 3rd edition of my book on impacted teeth.1 In the present context and according to Wikipedia, it refers to a developmental disturbance in shape of the tooth, with an angulation, or a sharp bend or curve, in the root or crown which is thought to be due to trauma during the period in which tooth is forming. The result is that the position of the calcified portion of the tooth is changed and the remainder of the tooth is formed at an angle. The curve or bend may occur anywhere along the length of the tooth, sometimes at the cervical portion, at other times midway along the root or even just at the apex of the root, depending upon the amount of root formed when the injury occurred. It often follows traumatic injury to the deciduous predecessor in which that tooth is driven apically into the jaw.

Fig. 1. An 8 year old female with an impacted and dilacerate left central incisor in a spaced dentition. The right central incisor has migrated slightly to the left, but the left lateral incisor has tipped mesially to within a couple of millimeters from the midline.

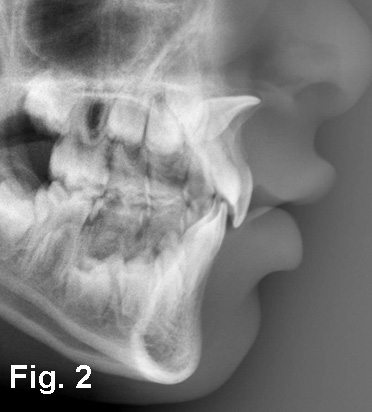

Fig. 2. The lateral cephalogram of the same patient shows a normal inclination of one of the two maxillary central incisors, while the orientation of the crown of the second is more than 90 degrees rotated upwards and posteriorly and is outline in the anterior nasal spine.

The “classic” central incisor dilaceration

In its “classic” form (Fig. 1), there is a distinct pattern and dilacerate incisors vary little between one patient and another. During the clinical examination, the apical third of the root may be palpated in the palate and the crown will be palpable very high up in the anterior nasal spine, literally in the root of the nose (Fig. 2). The root portion is in the form of a tight but regular curve in the antero-posterior plane with little or no displacement in the lateral plane.

Perhaps the most incredible attribute that belongs to this grossly deformed and ectopic tooth is that it has a normally shaped crown, which is the exact mirror image of that of the adjacent, erupted, central incisor. This feature, above all, makes it desirable for the practitioner to think in conservative terms, with the aim of finally placing this crown adjacent to its contralateral homologue as an essential constituent in the rehabilitation of the patient’s dental display, smile and self-esteem.

The causative injury will have occurred when the child was around 2 years of age. It may not have been a very severe blow and it may not necessarily have resulted in the loss of its deciduous predecessor. As the result and in a good number of cases, the incident may not have been remembered by the parents when the diagnosis is made, which will usually be at least 5-6 years later. Thus, a negative history will be recorded. Despite the fact that children of this age fall and traumatize their deciduous incisors quite frequently, this form of dilaceration is very uncommon. This is because the direction of delivery of the blow is probably far more critical as a factor than its absolute force – so critical, in fact, that bilateral occurrence is almost unknown.

The interesting point to be made here is that, in those patients who are diagnosed with a dilacerate central incisor at the age of 8, radiographs that had been taken at the time of the original trauma, at 2 years of age, show no displacement. This is in direct contradiction to the theory quoted by Wikipedia that the abnormal orientation of the coronal portion of the tooth occurred immediately following and as the direct result of the trauma. It seems that the force of the blow does not result in actual physical displacement of the tooth within the follicle. Notwithstanding, this view (sic) was and, possibly, still is standard teaching regarding the etiology of the anomaly. A much more logical theory has been proposed, which is presented here.1

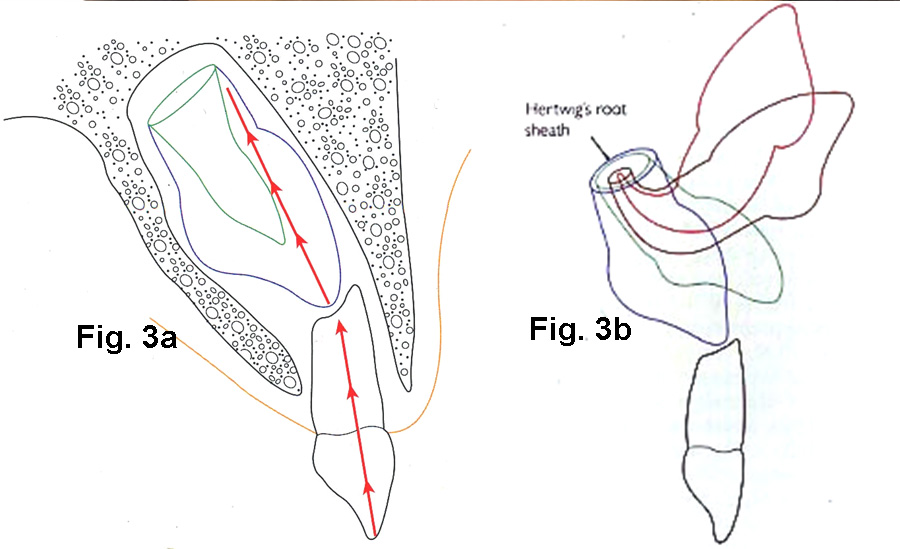

Fig. 3a. A diagram to show how a vertically directed force through the deciduous incisor is transmitted to the labial aspect of the mineralizing root of the unerupted permanent incisor. (This diagram appears in the second edition of the author’s text “The Orthodontic Treatment of Impacted Teeth” and is published here with the permission of Informa Healthcare)

Fig. 3b. A diagrammatic illustration of the progressive alteration in the orientation of a dilacerated incisor, during the disturbed root formation. Note that the position of Hertwig’s proliferating root sheath remains unaltered. (This diagram appears in the second edition of the author’s text “The Orthodontic Treatment of Impacted Teeth” and is published here with the permission of Informa Healthcare)

For a classical dilaceration to be initiated, the blow to the vertically-oriented deciduous incisor must be directed fairly vertically, so that the impact is transferred to the incisal tip of the unerupted permanent incisor, which is located immediately above the resorbing deciduous incisor root apex. The force from a “well-directed” but not necessarily heavy blow is conducted upwards through the unerupted and developing permanent incisor, still in the same vertical plane, to the ring of cells known as Hertwig’s sheath, which is responsible for root growth (Fig. 3).

The crown of the permanent incisor is characteristically more labially tipped in the alveolus, such that the blow is conducted onwards to the labial side of the forming root. The new dentine that is being laid down is an exact copy of the shape and diameter of the ring of cells that comprises Hertwig’s root-forming sheath and, as such, its newly-formed edge is sharp. Any blow to the labial aspect of this sharp edge will concentrate the force on the cells of the labial side and damage them. Their dentinogenetic potential becomes compromised and they produce dentine at a markedly reduced rate. An imbalance of dentinogenesis is thereby generated, with the healthy lingual remainder of Hertwig’s root sheath continuing to produce dentine at its normal rate. Instead of a straight and tapering root being generated, therefore, the outcome is a root which is curved labially, with the crown of the tooth being rotated in an ever increasing superior and posterior arc of circle, for as long as root development continues (Fig. 4). Viewed from the lateral aspect, such a tooth will describe anything up to a half circle.

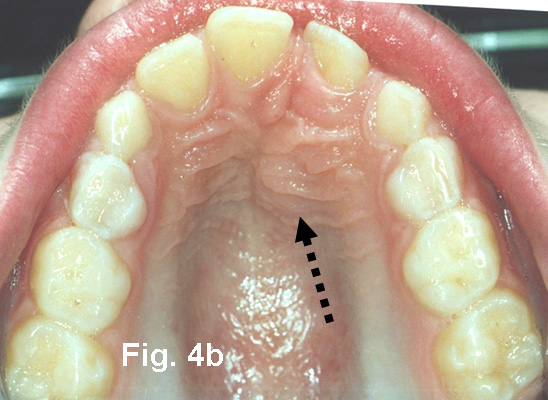

Fig. 4a, b. Anterior and occlusal views of another female, aged 12.6 years, with an impacted and dilacerate left maxillary central incisor, seen initially in February 2002. Note how far the right central incisor has crossed the midline and, together with the left lateral incisor, has encroached on the space of the affected tooth from both directions. The arrow points to the palpable bulge in the palate due to the presence of the apical area of the root of the dilacerate incisor.

Why is it important to understand etiology?

How this type of dilaceration occurs is very special and it governs the rationale for the treatment for its resolution. If the orthodontist does not recognize the fact that the crown of the incisor moves progressively upwards and backwards, how and why it continues under its own steam and in the wrong direction, he/she may be tempted to re-open space in the immediate area and then proceed to await spontaneous eruption. When that fails, open surgical exposure might be tried, with the misguided expectation that its position and orientation will improve autonomously…….. and the reader is invited to try to imagine what the surgical procedure might entail to get up there in the root of the nose and to achieve an opening high in the sulcular oral mucosa that would not close over within a few days!

Then you have the much later

problem that, if active traction is successfully applied to the tooth and full

resolution is achieved before its apex has completely closed, any further apical

root development that may subsequently occur will generate a force for relapse

and a resumption of the curved upward and backward rotation of the crown.

.

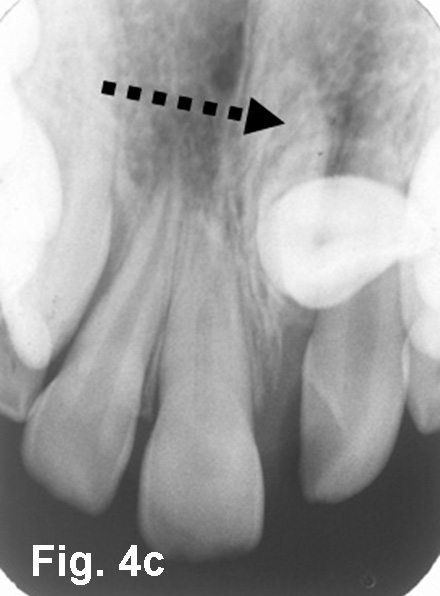

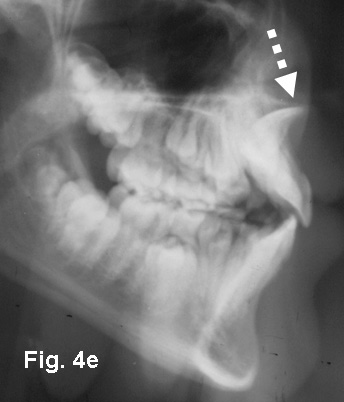

Fig. 4c-e. Periapical, panoramic radiographs and lateral cephalometric views of the second patient. The middle portion of the panoramic film has been “Photoshopped” to clearly view the typical dilacerations. Dental development is late, with a dental age of approximately 10-11 years. The crown of the affected tooth on the periapical film is seen in its long axis, while the arrow points to the bucco-lingual orientation of the apical region of the root of the tooth.

Treatment planning

The recommendations for treatment that are presented here are not based on disciplined scientific investigations conducted on a large group of patients suffering from this condition and treated by 2 or 3 different clinical methods, with suitable controls. They are, however, based on many years of clinical experience, during which patients have been followed up into their 3rd decade of life, often as much as 10 years or more post-treatment. The approach is not presented as the sole panacea for treating these teeth and it should be understood that alternative methods exist which may also produce satisfactory results.

The overall rationale is for a two-phase treatment protocol, which is recommended because:-

a. the diagnosis is usually established at age 7-8 years and there is frequently considerable pressure on the part of an anxious parent and sometimes of the child, too, to deal with the unsightly display of tipped, irregularly-sized, midline-traversed and asymmetrically-arranged teeth in the front of the mouth.

b. at this age, there are still 2-3 years ahead during which the apical region of the tooth will continue to develop and to worsen the degree of upward and backward displacement of the crown of the tooth.

Treatment of the incisor alone

will take approximately 2 years, during which time there is no real possibility

of treating the remainder of the malocclusion, because the dentition still comprises

a large number of unerupted permanent teeth.

There is a long list of problems that require to be addressed in the formulation of a treatment plan. These relate to technique and timing of surgical exposure and orthodontic biomechanics and ways to optimize the periodontal prognosis.

- the tooth, the whole tooth and nothing but………… ? It is clear from the outset that, if we are to align the facial surface of the beautifully shaped crown of the dilacerate incisor in its ideal orientation, the labio-lingual width of the alveolus in the incisor area may be too narrow to accommodate the curved root. For the crown to be placed in its position, the labial curvature of the root could hypothetically bring its apex through the periosteum and mucosa and well into the upper lip. It becomes obvious that an apicoectomy and retrograde root canal treatment will be de rigueur in all but the mildest forms of dilacerations.

- Is an open surgical exposure procedure the right way to go, or would a closed procedure be more suitable? Perhaps we need more than one exposure. When should the apicoectomy be performed?

- What orthodontic means can be used to resolve the impaction? Will a regular multibracketed appliance be suitable? Is it G.C.P. (good clinical practice) to engage the ectopic tooth in the same archwire that links all the other teeth?

- What is appropriate timing for orthodontic treatment and perhaps it should be done only in the permanent dentition stage?

- Should all the needed labial root torque be carried out in phase 1, or should some be left till phase 2?

- At what point should we stop phase 1 treatment?

- What should be left for phase 2 treatment?

- How do we deal with retention and assess the prognosis?

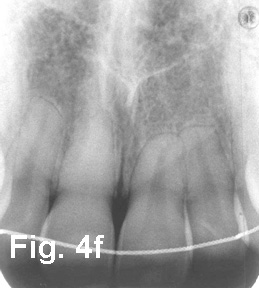

Fig. 4f, g. The periapical and panoramic views at age 20.5 years and 7 years post-treatment in March 2011 show treatment completed without the need for root treatment and apicoectomy. The pulp chamber of the right (unaffected) central incisor has completely obliterated, causing a yellow tinge in the color of the tooth. There has been no deterioration in the condition of the dilacerate incisors and there would appear to be every reason to expect it to last for many more years.

Fig. 4h-j. The teeth in occlusion at 7 years

post-treatment. Note the excellent incisor alignment, gingival heights,

adequate root torque.

Fig. 4k. The labial sulcus shows no sign of the root apex

of the incisor, indicating a relatively minor degree of root form alteration,

despite the severe initial displacement. Accordingly, there was no need for

apicoectomy and root treatment in this case. The yellowish color change in the right (unaffected) central incisor is due to the obliteration of the pulp, whhile the left, dilacerate central incisor has a normal color.

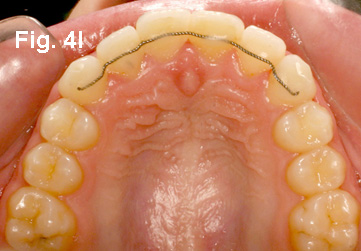

Fig. 4l. The view from the occlusal aspect, with the original twistflex bonded splint still in place.

Is it worth the effort and what are the alternatives?The best case scenario at the end of this chain of problems finds the patient with an apicectomized and root-filled central incisor which will hopefully last and function into adulthood, although with a more apically-located dilaceration, this can be avoided……. but the patient has all his own teeth….. and that is not all. If the various stages are performed well, the results should make it difficult even for a dentist to distinguish which was the dilacerate tooth (Fig. 4)

With this conservative approach, there are no artificial substitutes, implants, crowns or veneers, all of which have a “sell by” date. Certainly, if and when the tooth fails, it will need to be replaced by an implant. Nevertheless, by bringing the dilacerate tooth into the dental arch and, if carefully and conservatively handled in the surgical phases, it will be accompanied by a generous quantity of alveolar bone, which will serve the patient well at implant time. Long term experience with these cases, however, has shown that these treated incisors have a much longer useful life, both functionally and esthetically, than may have been thought possible at the commencement of treatment (Fig. 4f-l). Implants may provide short term gratification, but they do not last forever, and delaying their placement for 10-20 years or more is a major victory for the conservative approach. Do you know a prosthodontist who is prepared to guarantee his implant-borne restorations for longer?

Alternative #2: Extracting the incisor brings with it problems of its own. In the first place and even before the extraction, the alveolar ridge in the immediate area is already deficient both in terms of height and width. Following the extraction, the ridge becomes more deficient and, with an eye to the future, will present technical difficulty and a poor prognosis for the placement of an implant, which cannot be installed for another 12-15 years. In the meantime, space will need to be made and maintained with some form of removable denture or resin bonded bridge, both of which will inflict collateral damage on the hard and soft tissues, in the long run.

Alternative #3: Extracting the affected tooth and substituting the adjacent lateral incisor creates other problems. It is difficult to correct the midline and to draw a small tooth with a narrow neck into the place of the central, to raise its gingival height and then to alter its shape prosthetically, to match that of the beautiful and virgin contralateral central incisor. Then the canine must be brought into the place of the lateral incisor, its shape altered, its labial bulge torqued lingually and its high gingival attachment lowered to lateral incisor height. Turning the premolar into a canine is perhaps the easiest part of this disguise/masquerade/simulation. For most of us mortals, the results are not always encouraging. For a really good result, you and your prosthodontist need to be able to reproduce the kind of expertise for which Zachrisson and Toreskog have come to be known.

Reference:

Becker A. The orthodontic treatment of impacted teeth. 3rd edition. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell Publishers, March 2012

In next month’s Bulletin #11 May 2012, the practicalities of the treatment of dilacerated incisors by the approach that is recommended here, will be discussed and illustrated in full clinical detail.